By Larry Doornbos

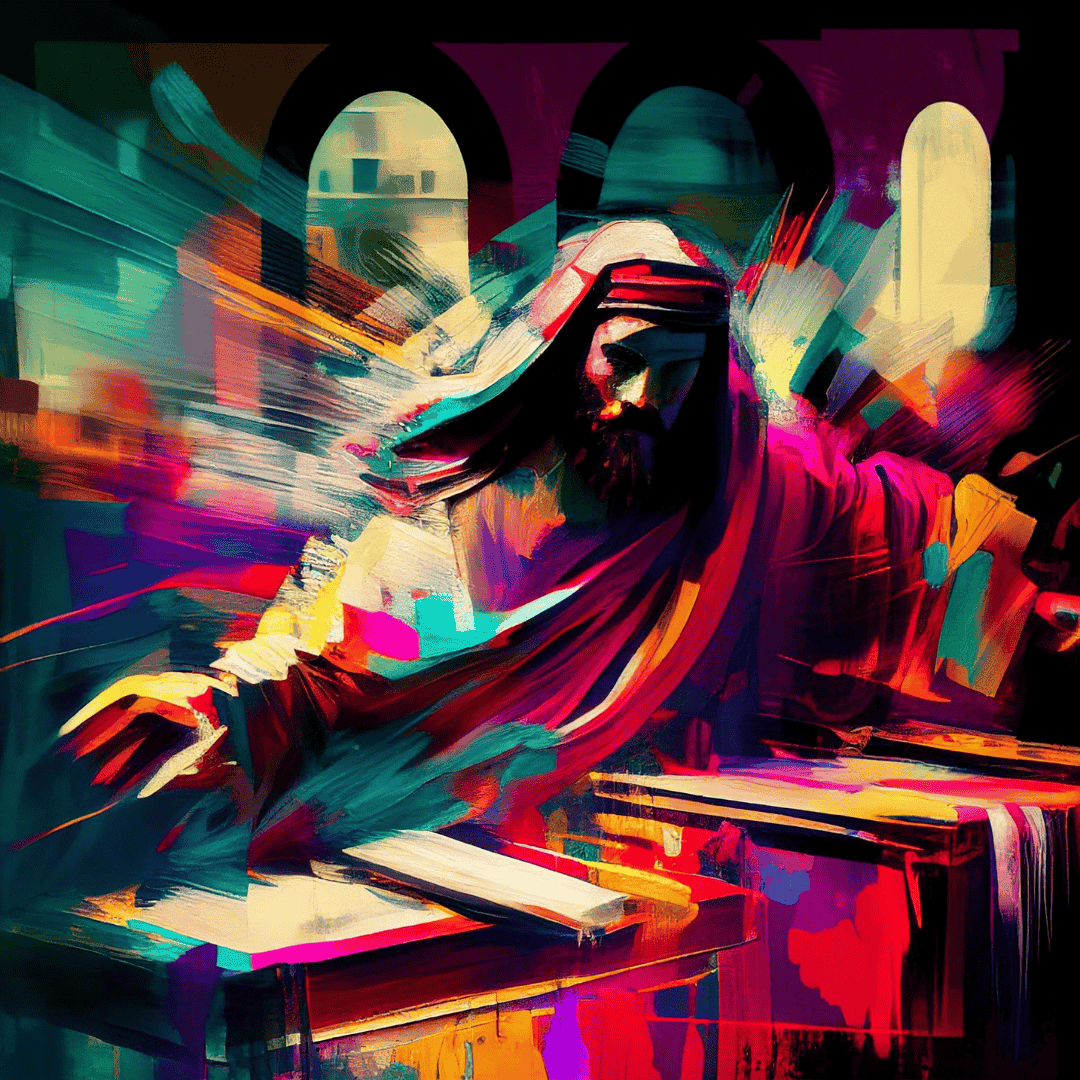

April 16, 2024The Last Supper.

We scan the faces at the table seeing the 12 disciples and Jesus.

But who’s really at the table?

Fishermen who are considered the middle class of their day.

A tax collector who likely ripped fishermen off and who supports Rome.

People with Jewish and Gentile names—are they less than fully committed to Jewish ways?

A zealot who wants Romans dead.

Those sitting at the table by all earthly measures shouldn’t be together.

But Jesus forms them into a kingdom movement. Jesus breaks down the barriers between them—status, sect, nationalism, commitment to the empire. This is the beginning of a community that changes the world. As those who opposed Paul said in Thessalonica,

“When they could not find them, they dragged Jason and some believers before the city authorities, shouting, “These people who have been turning the world upside down have come here also, and Jason has entertained them as guests. They are all acting contrary to the decrees of the emperor, saying that there is another king named Jesus.” (Acts 17:6–7 NRSV)

The disciples around the table and Paul have let go of old allegiances. Their new allegiance is to Jesus and his kingdom. Their pledge of allegiance might sound something like this, “I pledge allegiance to the Lamb and the kingdom for which he stands”.

Michael Goheen gives insight into the nature of this community:

Newbigin says that it is “not the primary business of the Church to advocate a new social order; it is our primary business to be a new social order.” He offers four characteristics of such a community:

praise and self-giving love amid selfishness,

mutual acceptance amid autonomous individualism,

mutual responsibility amid a demand for rights,

hope amid despair and consumer satiation.

“When that hermeneutic is available, people find it possible to have a new vision for society and to know that the vision is more than a dream.” (The Church and Its Vocation: Lesslie Newbigin’s Missionary Ecclesiology)

A vision that is more than a dream. A community that is a picture and foretaste of God’s new society. A community that pledges allegiance to the Lamb, to his kingdom, and lives out that allegiance.

Sadly, we often find it difficult to live out the vision. We find it difficult to break down the dividing walls of hostility. Rather than gathering around the table as a new community, we are often determined to hold on to our divisions. Rather than being a picture and foretaste, we give a picture of brokenness and a taste of disunity.

For Jesus and the kingdom for which he stands this is a deep grief. As Goheen writes,

This is why Newbigin denounces disunity in such impassioned language, calling it

“a direct and public contradiction of the Gospel,”

an “intolerable offense against the very nature of the church,”

“something illogical and incomprehensible,”

“a plain denial of the Gospel,”

a “public abdication of [the church’s] right to preach the gospel to all nations,”

an “intolerable scandal.”

…disunity is scandalous because it contradicts the church’s message—the good news is that in Christ, God is reconciling the world to himself.

So mission is dependent on unity, and unity is dependent on mission. When the church does not grasp its missionary vocation, it is minimally concerned about unity.

Newbigin believed the only way to account for the “astounding complacency” toward a divided church that “so plainly and ostentatiously flouts the declared will of the Church’s Lord” is the loss of a missionary understanding of the church.

Before we can live out the characteristics of a community that pledges allegiance to the Lamb, we have to recapture our missionary understanding of the church. A missionary understanding that speaks of the church as being a picture and foretaste of the kingdom. It is not enough to speak of unity or to propose a dream of unity, the church needs to give a picture and foretaste of that unity. To fail to do so is to fail both our missionary calling and our missionary being.

Our reality is we are too willing to set aside our missionary calling and our missionary being. We are quick to divide and slow to find ways to come together. We look for the wedge issues that show we are better or more faithful than others. The words of Paul to the Colossians shape us to:

“Bear with one another and, if anyone has a complaint against another, forgive each other; just as the Lord has forgiven you, so you also must forgive. Above all, clothe yourselves with love, which binds everything together in perfect harmony. And let the peace of Christ rule in your hearts, to which indeed you were called in the one body. And be thankful.” (Colossians 3:13–15 NRSV)

But what if our belief in our faithfulness actually shows a lack of faithfulness? What if our willingness to divide shows a failure to understand our calling as a missionary church? A missionary church that calls people to be reconciled to God and lives as a reconciled community so showing the amazing unity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit (see Ephesians 2, Revelation 4-5).

What if our very belief that we are being faithful (however we define that) destroys our calling as a missionary church (John 13, 17, Acts 1)?

On the other hand, when we live our missionary calling by being a picture and foretaste of a unified kingdom community that turns the world upside down, the words of Jesus resound.

My prayer is not for them alone. I pray also for those who will believe in me through their message, that all of them may be one, Father, just as you are in me and I am in you. May they also be in us so that the world may believe that you have sent me.” (John 17:20–21 NIV11)

Questions for Reflection and Action

How can your congregation regain the missionary understanding of the church?

Can working toward Newbigin’s four characteristics of a new social order begin to build unity in your congregation?

Can this be a start toward your congregation being an alternative kingdom community?

What would taking Newbigin’s words to heart and working to live them out diligently do for building unity in our congregations, classes and denomination?

Written by Larry Doornbos