By Dr. Wayne Brouwer

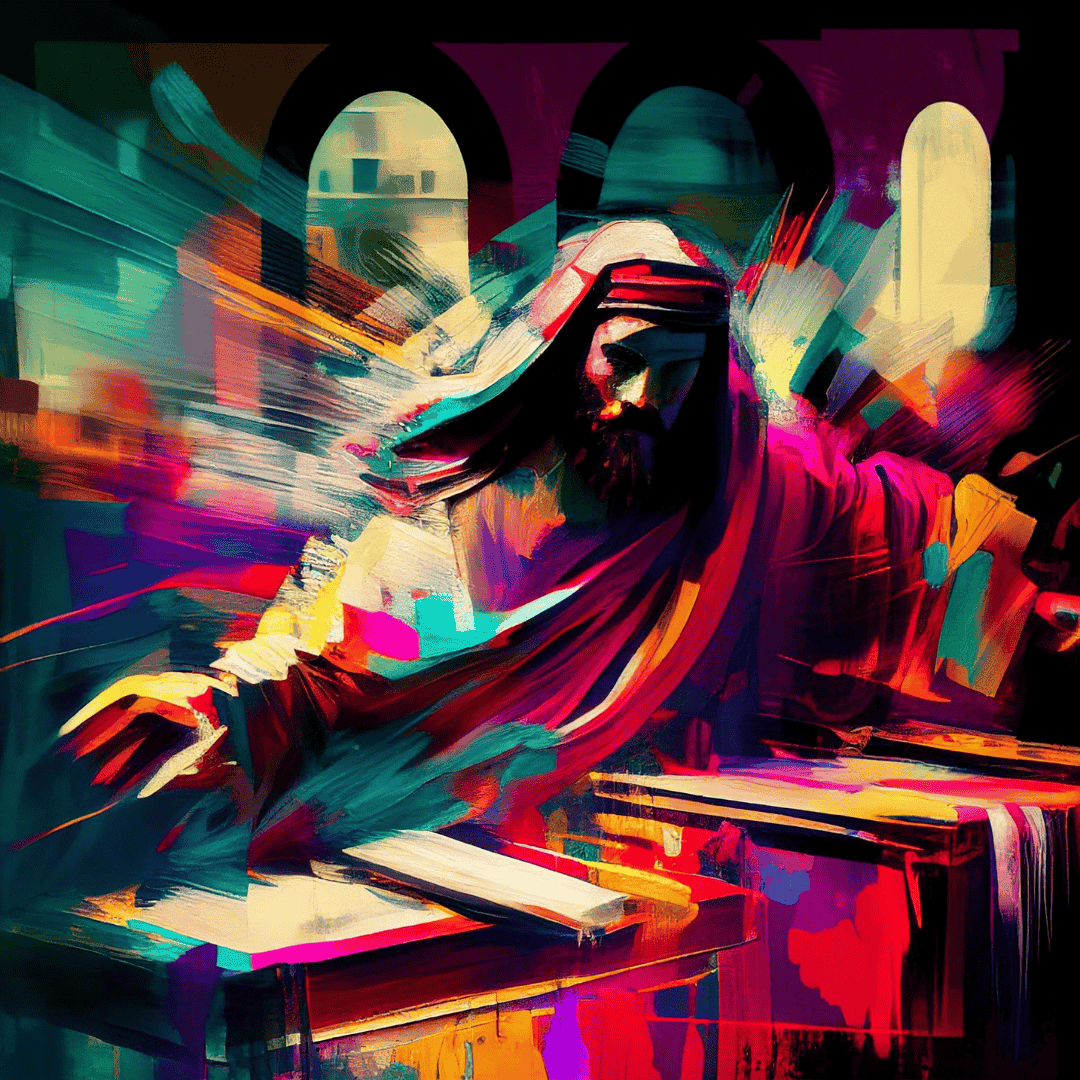

March 15, 2023Madeleine L’Engle’s fine story Dance in the Desert begins with a caravan of people traveling in hurried fear through a trackless wilderness. They seem to be running from something, and turn furtively to check the movement of shadows at the edge of their peripheral vision. Particularly noticeable among them is a young family, a husband and wife along with their tiny boy.

Night falls and the travelers establish a camp. All gather around the huge bonfire which is lit as a repellent to the darkness and whatever beasts and demons it might hold. From huddled security near the flames, the community shivers at growls and hisses that emanate from the unseen world beyond the licking of the fire. Now and again the piercing reflection of strange eyes looks at them out of the black void and they quickly turn back to comforting small talk which helps them pretend at safety.

But they will not be left alone. The shrieks and warning snarls edge closer. Then a paw appears, or a sniffing nose, only to be withdrawn before spears can poke or arrows be aimed. More faggots are thrown on the fire.

Yet the beasties and wild things will not be stopped. Growing more daring, a bear steps into their circle and a bold viper slithers in from the other direction. There is panic in the camp as all scatter and leap and search for weapons. In the commotion the young husband and his younger wife are separated, each believing the other has grabbed their little boy to safety.

But the child was left behind. He faces the wolf and the lion and the bear and the snake and the other wilderness creatures alone. Only there is no distress in his voice, no panic in his cry. Instead, he coos and clucks with delight at these mighty furry and scaly toys that have come to play. He claps his hands and bounces his feet and giggles with animation.

As the caravanserai is suddenly pulled from its panicked zigzagging by the tinkle of the child’s good humor, all the adults stop and turn, expecting the wild things to tear limb from limb and demolish this human plaything they have abandoned. But it is not so. Instead, the child has brought some kind of intelligent direction to its strange play. His chubby arms are actually orchestrating a symphony of animal cries, and his hands are directing the choreography of a marvelous beastly dance. The bear is on its hind legs, not to swipe and strike but to gyrate with the tempo of the child’s clapping. The snakes slither in pairs forming artistic designs in the desert sands. Above, the vultures and hawks swoop and turn and bank and dive in aviary formation. The lions and tigers nod their heads as if in rhythm to celestial instrumentation.

Slowly, and with mesmerizing fascination, the adults creep back to their places by the bonfire. They become the audience in the greatest show on earth. The child whoops and tips and giggles and sways and claps his hands in time with the music of heaven, and the animals of earth dance around him with delight. Even the big people begin to hear transcendent melodies, and the night has become as friendly as dawn or daylight.

Eventually the child tires, as all children do, and the cooing stops, the clapping ceases, and the animals slink away. But they are no longer predators, and the fear of both man and beast has vanished. All that is left is the Child. And those who linger in awe know that there is a new center of gravity in the universe.

We know that Madeleine L’Engle is imagining a mythical moment on the travels of Joseph and Mary and young Jesus from Egypt to Nazareth, as told briefly by Matthew in his gospel. But the scene has parabolic power. I cannot reflect back to all of you today what storms and beasts and dark places you are fearing. You know them all too well. They have become, for some of you, a house of horrors from which you would move if you could but you can’t. You step out into the weather of each morning wearing a façade of faith and trust, believing you are able again to walk on water. Yet too often, before the day is half finished, and often in full sight of your friends and co-workers traveling with you, you slip and slide and sink.

I do not have any quick-fix solutions for you, no faith waders, no emergency life rafts or instant pontoons. All I can say is what the New Testament often affirms. You’ve got to keep your attention focused on Jesus. Not as an iconic talisman, but as the center of meaning around which everything else begins to revolve and resonate.

Leaders are not immune to dark bouts of depression or ominous threats from the beasties of this world that crawl from ungodly shadows. That is why we at CLC try to encourage leaders, mostly in the sunshine strength of their good careers, but sometimes in the bleaker moments when it seems like they cower alone.